* People in the high-altitude Maqu County, in northwest China's Gansu Province, prefer to use grids made of red willow in fighting desertification. Red willow grids, which offer more durable features, are able to adapt to high-altitude environments characterized by cold weather, scorching sun, and frequent wind and rain.*

To further preserve the ecological environment of Maqu, people also explored appropriate shrubs and grasses to grow in the sandy soil surrounded by the red willow grids, in an effort to increase vegetation and provide windbreaks. The county has launched a series of policies to encourage herders to graze in an orderly manner -- so that pastures could be given time to recover.* Through arduous efforts, Maqu had by the end of 2022 managed to establish windbreaks along riverbanks, covering an area of over 1,406 hectares, which is equivalent to 1,970 standard soccer fields. Annual outbound water flow from the Yellow River in Maqu totaled 15.74 billion cubic meters in 2023, a 27.4 percent increase compared with 2020.

LANZHOU, Oct. 25 (Xinhua) -- Grass grids made of wheat straw, which stabilize sand, mitigate wind erosion and retain moisture, are considered effective tools in the quest to combat desertification. However, people in the high-altitude Maqu County, in northwest China's Gansu Province, prefer to use grids made of red willow in fighting desertification.

Maqu of Gannan Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture in Gansu is located at an average altitude of over 3,300 meters on the Qinghai-Xizang Plateau, featuring vast pastoral areas.

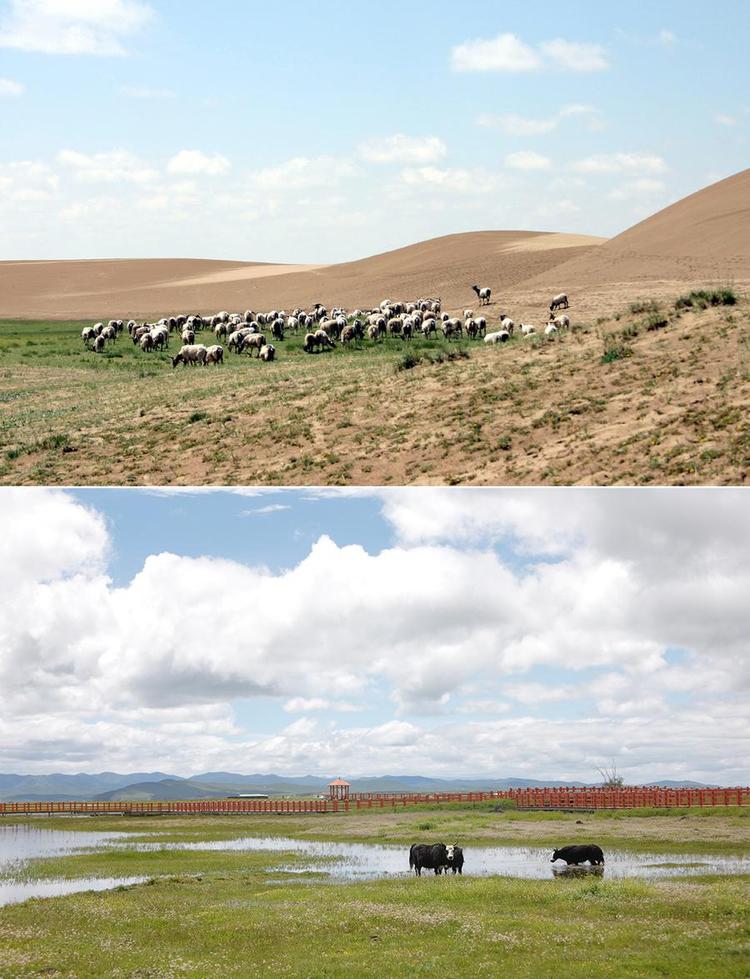

Through exploring appropriate sand-fixing method and windbreaks, and enhancing pastoral management, the county's sandy desertified area has nearly reduced over 46 percent since 2012.

China, one of the countries with the severest desertification, has made significant progress in curbing the expansion of deserts, taking the lead in achieving zero net land degradation worldwide.

From 2009 to 2019, desertified land in China had a net decrease of 50,000 square km, a significant change compared with an expansion of 3,436 square km a year at the end of the last century, according to China's National Forestry and Grassland Administration.

Desertification is among the most pressing global environmental challenges, while fighting an uphill battle against desertification in plateau regions requires even more arduous efforts.

ARDUOUS COMBAT

Maqu means Yellow River in the Tibetan language and refers to China's second-longest river, measuring 5,464 km in length. A meandering section of around 430 km of this river is in Maqu County.

According to Maqu historical records, when there was flooding in the Yellow River, grasslands in Maqu adjacent to river courses would be inundated while sand would be left there after the water receded.

Frequent changes in the course of the Yellow River and overgrazing also led to a gradual spread of desertification in the county. In 2012, the size of the sandy desertified area in Maqu had reached about 53,333 hectares -- about 5.2 percent of the county's total.

To tackle desertification, locals first set up straw grids, but soon found that such grids were not robust enough to prevent desertification in Maqu. After multiple trials, they found an effective tool in the form of red willow grids.

Grids made of red willows, which offer more durable features, are able to adapt to high-altitude environments characterized by cold weather, scorching sun, and frequent wind and rain, said Ma Chunlin, 33, an official with the natural resources bureau of Maqu.

For nine years, Ma has worked with the local professional desertification control team in spring, first setting up straw grids before later switching to the more effective red willow grids, which have been cultivated extensively since 2020. Ma said he often experiences altitude sickness, while his skin and clothes are regularly pierced or torn by red willow branches.

"Setting up these red willow grids is much more labor-intensive than straw ones," he said. "My wife helped me to sew my pants almost every day after work."

Currently, Maqu has managed to restore over 24,793 hectares of previously sandy desertified land. As of the end of 2023, comprehensive vegetation coverage of the county's grasslands had reached 98.4 percent.

"About 20 to 30 years ago, the grassland was sparse, and sand was blown into my nose and hair," said Jigshi Tsering, a 53-year-old herder living near the Yellow River in Maqu, while adding that "in recent years, there is no more such wind and sand, and our grassland is now green and prosperous."

SUITABLE PLANTS, METHODS

To further preserve the ecological environment of Maqu, people also explored appropriate plants to grow in the sandy soil surrounded by the red willow grids, in an effort to increase vegetation and provide windbreaks.

Just over 10 years ago, Maqu officials had visited other parts of Gansu to learn more about sand control practices, and they brought back drought-resistant shrubs like saxaul and sweetvetch to serve as windbreaks.

However, the experience of other areas did not prove successful in sand control in Maqu, as the plants obtained there by Maqu officials proved to be appropriate only for relatively low-altitude regions.

"We planted saxauls and they did grow. But they did not survive heavy snowfall in winter," said Ma Jianyun, a forestry technical service expert in Maqu.

He added that locals also tried planting just grasses, but the grasses had failed to survive without the protection of shrubs.

After failing repeatedly, locals decided to cultivate both grasses and shrubs together in red willow grids, doing so on a trial basis. The outcome of the trial was positive and a systematic approach was then adopted, which has been promoted significantly since 2020, according to Ma Jianyun.

Ma Jianyun explained that grasses are first planted at the inner edge of red willow grids, with organic fertilizer added as well.

"Annual grasses can stabilize the sand in the first year and grow tall enough to protect perennial grasses. By later years, when perennial grasses have grown, annual grasses can serve as nutrients for their growth and no longer need to be planted," said Ma Jianyun.

Shrubs such as salix and sea buckthorn, which require larger spacing, are cultivated in the inner part of grids, Ma Jianyun said, adding that these shrubs have better survival rates on the plateau, and are resistant to sunlight, while also protecting grasses from strong winds. Residual spaces inside grids are also filled with grasses again.

Ma confirmed that this systematic approach has established operational standards -- achieving a plant survival rate of over 95 percent.

Recovery of desertified grasslands generally takes three to five years, requiring vegetation coverage of over 60 percent, so that basic sand control standards can be met.

Through arduous efforts, Maqu had by the end of 2022 managed to establish windbreaks along riverbanks, covering an area of over 1,406 hectares, which is equivalent to 1,970 standard soccer fields. Annual outbound water flow from the Yellow River in Maqu totaled 15.74 billion cubic meters in 2023, a 27.4 percent increase compared with 2020.

In addition, Maqu officials communicated with herders, explaining the importance of timely reseeding and fire prevention measures in winter, while also opting to raise and reinforce levees along the Yellow River to minimize the potential for erosion.

PASTORAL MANAGEMENT

In the past, local herders believed that the more cattle and sheep one owned, the greater one's wealth and social status would be. However, experience has shown that overgrazing is often counterproductive.

Tobgye Rinchen, head of a yak breeding base in Maqu, recalled his family raising more than 300 yaks. However, despite the growth in their yak numbers, they found that their income did not increase much.

"At that time, yaks grew slowly and we worked more but unit profit was less. Meanwhile, the grassland was deteriorating day by day," Tobgye Rinchen said.

As a result, the county government decided to launch a series of policies to encourage herders to graze in an orderly manner -- so that pastures could be given time to recover.

According to the local grassland-livestock balance policy, which determines livestock numbers based on grassland carrying capacity, about 1.07 hectares of grassland is needed to breed one head of cattle and some 0.27 hectares to support one sheep.

Livestock in the county has been reduced by over 651,100 sheep units (a cattle unit equals four sheep units) since 2021.

Tobgye Rinchen said the number of yaks owned by him has dropped by about 50 percent to around 150. Notably, thanks to more intensive and efficient breeding methods, such as dry-lot feeding, the growth cycle of yaks in the county has been shortened from about seven years to around four years.

"Our turnover has become faster and the meat is more tender," said Tobgye Rinchen.

There are currently more than 800 breeding bases raising yaks in Gannan, with the proportion of yak production volume in captivity increasing from nearly none in 2021 to over 15 percent at present.

A reduction in sandstorms combined with greener grasslands in Maqu has resulted in more tourists being attracted by its idyllic pastoral life and appealing Yellow River scenery. Gannan recorded more than 22 million trips from domestic and foreign tourists in 2023, and earned comprehensive tourism revenue of 11 billion yuan (about 1.54 billion U.S. dollars), increases of 52 percent and 49 percent, respectively, compared with 2019.

"Lucid waters and lush mountains are invaluable assets. The high-altitude ecosystem is fragile and interconnected, requiring a coordinated, strategic approach," said Yang Zhiming, county head of Maqu. "Ecological protection is an endless work, and we will continue to make our grassland greener."

(Reporting by Zhao Chenjie, Song Changqing, Zhang Qin, Cui Hanchao, Zhang Zhimin; Video reporters: Zhang Li, Zhang Qin, Zhang Zhimin, Cui Hanchao, He Wen; Video editors: Zhang Li, Li Qin, Luo Hui, Zhang Yuhong)

编辑:徐璇